The Story of the Birth of the Iron Workers - Episode 1

I have been meaning to write this article from the viewpoint of Tetsuro, but I have not done so, so I will start today.

I would like to start by asking when the Tetsuro organization was founded and what kind of union it originally was.

Japan National Railways Labor Union

Iron Workers' Union was also originally an organization separated from the National Railway Workers' Union

First of all, I would like to say that Tetsuro and Doyo, as well as Doyo, originally separated from the Japan National Railways Workers Union.

The first union to split off from the Japan National Railway Workers' Union was the Locomotive Workers' Union, which split in 1951.

It was the predecessor of Douro, and was a union consisting only of locomotive crew members and inspection and maintenance personnel. The moderate faction was the mainstream and maintained good relations with the employer side, supporting Torazo Kijima, who had served as the head of the operation bureau and managing director, as a candidate within the organization.

It was not until the 1960s that the Douro began to be eroded by the Revolutionary Marxists, but this is off topic, so I will omit it.

Now, as for the important Tetsuro, its roots can be traced back to the Niigata Struggle of 1957.

Since the Japanese National Railway Workers' Union was originally created by rallying most of the Japanese National Railways employees, the ideas of the union were mixed. There were groups that took instructions from the Communist Party, and there were also anti-communist groups that opposed the Communist Party's instructions. It can be said that at this point, the National Railway Workers' Union (NRW) was not a united body.

The Iron Workers were formed by a group known as the Min-do Right Faction

The Tetsuro was a union derived from a group within the National Railway Workers' Union called the Min-do.

The Min-do group was a group that supported the Japan Socialist Party (today's Social Democratic Party), but just as there were right-wing and left-wing factions within the Socialist Party, there were right-wing and left-wing factions within the Min-do group.

In 1957, a large-scale struggle took place in Niigata.

It started with the union's opposition to the dismissal of two workers during the June 13 struggle against the disposition of the National Railway Niigata District Headquarters, which was described as follows in our website When Japan National Railways existed.

(Quoted from the era when Japan National Railways existed, 1957)

Niigata Struggle, Japan National Railway Workers' Union, against the disposition of the authorities, entered the struggle on 7/9.

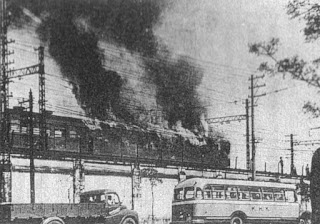

The struggle in Niigata, which began with the dismissal of two workers on July 9 as a result of a June 13 struggle by the Niigata District Headquarters of the Japan National Railway Workers' Union against the disposition of the authorities, was accompanied by on-the-job rallies during working hours and a strong law-abiding struggle, completely paralyzing freight transport across the Sea of Japan and causing service suspensions and delays to increase. The workers clashed with railroad security officials at various locations, and even received protests from farmers' representatives.

At a meeting of the Central Executive Committee held on the 16th, a vote was taken by 20-8 to issue an order to suspend the operation, and everything was transferred to the central committee.

The Kishi Cabinet was formed. Sannojo Nakamura was inaugurated as Minister of Transport.

The Niigata District Headquarters of the Japan National Railway Workers' Party (JNR) held workplace conventions at two stations, including Naoetsu, in response to JNR's spring action, and launched a struggle against the action.

As a result, back longitudinal freight transportation was paralyzed, and negotiations remained stalled even after the order to halt the struggle on July 16. Fujibayashi, Chairman of the Labor Committee of the Public Corporation of Fujibayashi, decided to initiate mediation.

In line with the JNR's move, the Niigata Branch of the Japan National Railway Locomotive Workers' Union (later the Douro) also joined the struggle, refusing to work overtime indefinitely and refusing to operate extra trains, etc. 7/11

Five more JNR strike participants arrested. All workplaces hold indefinite workplace rallies, and the situation becomes a quagmire, with the authorities refusing to back down.

All trains in the Niigata area are suspended. 7/16

Authorities add 15 more dismissals. 7/17

The Central Struggle Department orders the strike to be called off. 7/18

JNR authorities announce 4 dismissals in response to this dispute 7/18

Negotiations begin at the central level regarding the Niigata dispute, but discussions remain at a standstill. 7/19

Negotiations are underway between labor and management, but the authorities maintain a strong stance that they will not hesitate to confront the JNR head-on and request assurances from the union that they will not engage in discussions with the dismissed officers. The union side is in a situation where the mainstream faction (the Min Dong right faction) is being driven into a corner, and the situation is becoming unsettled, including the mutual intentions of the two factions.

In order to break the deadlock, Fujibayashi, chairman of the Labor Committee of the public corporation, has decided to launch mediation, but the authorities have maintained a firm stance that no collective bargaining will take place until union representatives other than the laid-off workers are determined, and have decided on the basic policy that the current collective agreement will expire at the end of its term as long as the union maintains the status quo. (Related: Authority, Deduction of Union Dues) (Related: Authority abolishes deduction of union dues, 10/23) The union has applied for a provisional injunction prohibiting the refusal of collective bargaining, claiming that excluding the dismissed executives from collective bargaining would be de facto recognition of the punishment they have long claimed to be unfair, and would also be inconvenient from the standpoint of internal unity since the major struggle has been suspended. There is no way out of this situation.

Furthermore, some of the union members are dissatisfied with the National Railway Workers' Union's campaign policy, and there is even a movement among them to form a non-industrial union to establish the right of collective bargaining and solve the immediate problem. Since the situation was not progressing at all, the National Railway Workers' Union came to the decision not to use any force to affect trains until September 25 anyway, and to develop the nationwide struggle from the end of September to the year-end struggle, as decided at the convention→Reference: The Struggle in Niigata

The second half of 1957, when the Japanese National Railways was in existence.

The struggle was quite powerful.

As a matter of fact, in 1957, the strong struggle had been repeated since around March, and the JNR authorities were quite aggressive in issuing disciplinary actions, which was a stiff confrontation considering the cozy relationship with the authorities seen after the Marusei Movement around 1975.

Under such circumstances, there was a movement among the non-working National Railway Workers' Union members (management bureau members) in Niigata to split because they could not sympathize with the movement of the National Railway Workers' Union.

Please also read the history of the Japanese National Railroad Labor Movement from the viewpoint of the National Railway Workers' Union.

Translated with www.DeepL.com/Translator (free version)

コメント

コメントを投稿